Clay slope overlooking the airfield and the River Mole; our Long-horned Bee nesting site

Within the broad topics of conservation biology and habitat management, schools of thought change as new science and experience comes to light. Conservationists must be open to feedback, analysing and reviewing their work, questioning the impacts and controversies of what they are trying to achieve. On Gatwick's sites, we have the added challenge of striking a balance between wildlife conservation and aerodrome safety.

Westfield Stream, airside. Areas closest to the airfield are kept as sterile as possible, reducing attractiveness to flocking birds or large mammals which could come in contact with aircraft

Horleyland Wood. Further away our areas are managed to encourage species diversity, perhaps even contributing in small ways to a push-pull dynamic for wildlife

The reality is that we are working with a large-scale operational hub incorporating many buildings, transport infrastructure and the people who operate and pass through it. Since the first bird strikes reported early on in aviation history, research on wildlife hazards at aerodromes has been a broad and contentious topic. It makes fascinating reading because almost every aerodrome has its particular set of circumstances presenting a unique case. Our ultimate priority is minding the safety of both wildlife and people when managing habitats around Gatwick, which means sometimes thinking outside the parameters of an idyllic nature reserve.

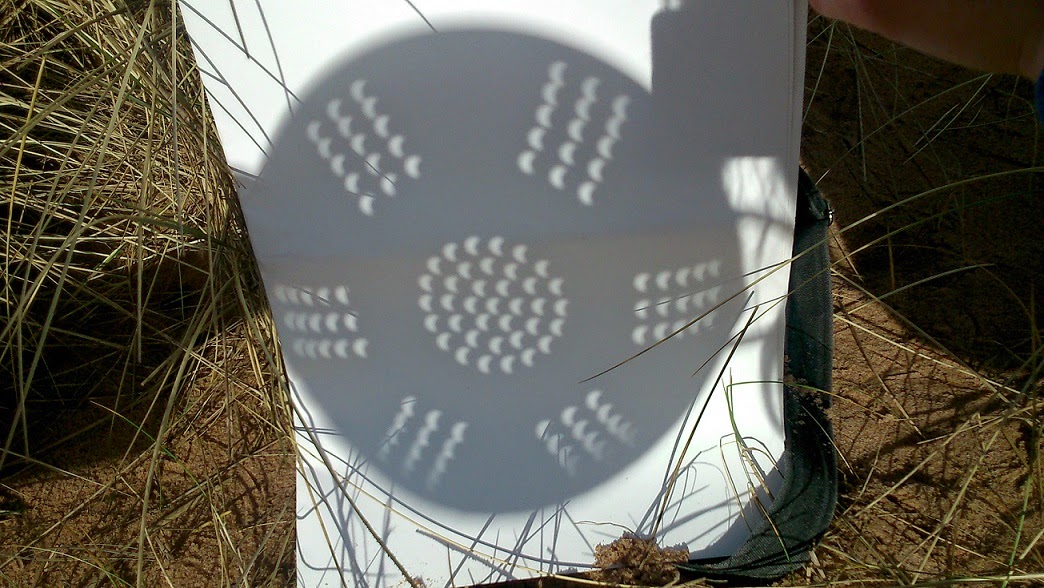

Ashley's Field. Showing the students our Grass Snake habitat enhancements and bee areas

The contrast of conservation management techniques was highlighted to the students after visiting the fantastic Knepp Estate Wildland Project near Horsham, West Sussex. This large landscape project (around 1,000ha) uses free-roaming grazing animals and the natural dynamics of succession to revert ex-agricultural land back into something more naturalistic. This practice of 'rewilding' is already producing some pretty exciting results at Knepp. On a much smaller scale at Gatwick, some of our areas have also been left to 'rewild', as small pockets of grassland which historically were used for pasture or agriculture were long ago abandoned as buffer areas around the airfield.

Scrub West of Brockley. Searching for rare Brown Hairstreak Butterfly eggs on Blackthorn - it took the students only a couple of minutes to find one of these tiny eggs

No easy task - these eggs are only around 1mm diameter

However, due to the much smaller sizes of our sites and their overall fragmented nature, we can't expect the same large-scale ecosystem dynamics to come into play. Instead we intervene through techniques such as manual scrub clearance, coppicing and re-planting to maximise the diversity of the land we have left, preventing a few species or habitats from becoming overly dominant. This means that even in a small area, we can maintain a wide variety of good habitats benefiting a wide range of species.

Working with a commercial entity has also taught us greatly about mediating between differing agendas; nature wants to perpetuate whereas infrastructure wants

growth, and often it would be the latter taking precedence over the former. Communication and information sharing is an incredibly important process in finding sustainable

ways going forward and to avoid repeating past mistakes.

North West Zone. Sussex University Biological Science Students and research staff

Tom Simpson and I would like to sincerely thank everyone who came along last Friday for this tour of our sites; it was quite gratifying sharing what we are doing with future ecologists, conservationists and researchers. Hopefully we can continue to establish links with academic and research institutions, providing training, research resources and further developing our airport biodiversity project.